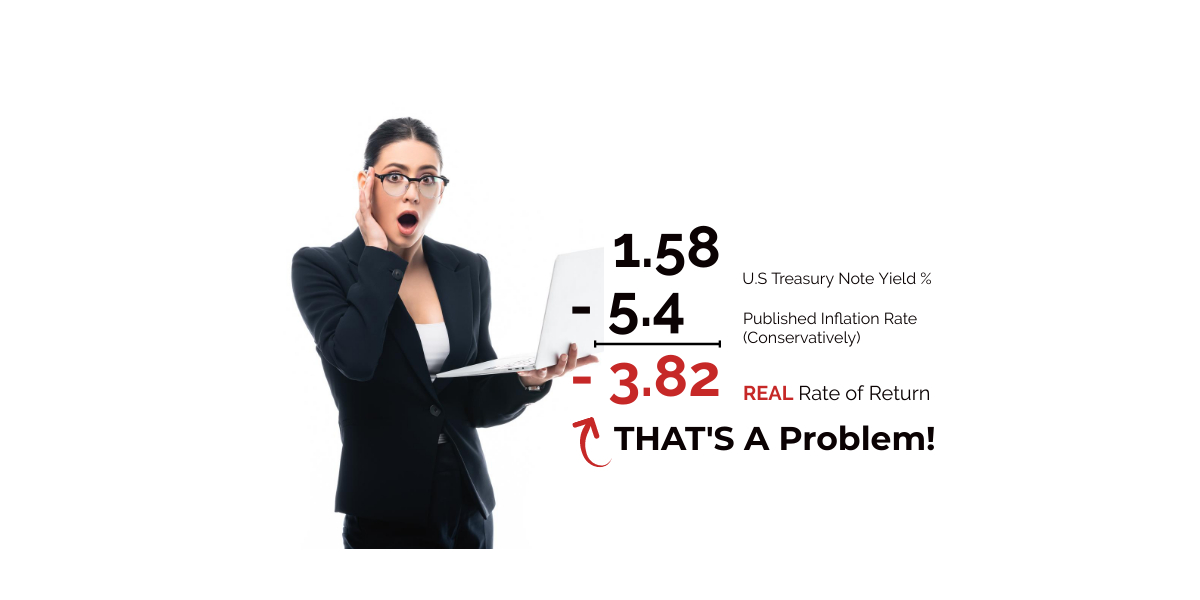

A period of global turmoil has put trust at the center of how people interpret news, markets, and policy. In this environment, two metrics are used as guiding measures: the yield on the U.S. Treasury 10-year note and the government’s published inflation figures. By subtracting inflation from the Treasury yield, one derives the real rate of return, a key indicator of purchasing power and savings viability. Today, those numbers point to a troubling reality: the 10-year Treasury yield sits at 1.58%, while official inflation runs at 5.4% annually. The resulting real return is negative, at approximately -3.82%. This negative gap implies that savers are losing purchasing power even as they set aside money for the future, a paradox in a system that depends on savings to fund investments, retirements, and growth. It is within this context that debates about monetary policy, debt sustainability, and market valuations unfold, raising questions about how economies can grow when savings are effectively penalized.

Understanding the North Star Metrics: Yields, Inflation, and Real Return

The concept of a “North Star” in this analysis rests on two observable, publicly reported metrics: the yield on the U.S. Treasury 10-year note and the government’s inflation figures. These two data points are not just numbers; they are the lenses through which investors, savers, and policymakers assess future risk, opportunity, and the relative value of various assets. The logic is straightforward: the nominal yield on a long-dated government security reflects the compensation investors require for deferring consumption and bearing duration risk, while inflation represents the erosion of purchasing power over time. When these two forces are combined through a subtraction—yield minus inflation—the result is the real rate of return. This real rate is a proxy for the net growth in purchasing power an investor can expect after accounting for price increases in the economy.

In the present context, the yield on the 10-year Treasury is 1.58%. The official inflation figure, as measured by the Consumer Price Index, indicates an annualized rate of 5.4%. By performing the subtraction, the real rate of return is -3.82%. It is important to note that other independent economists argue the inflation figure may be higher than the government estimate, but for purposes of this assessment the official figure is used. The magnitude of this disparity between return and inflation carries broad implications: savers face a persistent erosion of wealth, and the incentive to save may be weakened when the opportunity cost of holding money in safe assets outruns the gains from interest income.

This situation poses a direct challenge to the premise that low interest rates automatically promote growth. If savers are penalized by negative real rates, the supply of funds available for lending and investment could be constrained, even as governments rely on debt markets to finance expenditures and programs. The tension is intensified by the needs of long-horizon institutions such as pension funds, which depend on positive returns to meet future liabilities. Pension funds typically require yields closer to the order of 7% to remain viable and fully fund obligations to retirees. The arithmetic becomes problematic when these institutions are required to invest in government bonds with a real return that may be negative or constrained by low nominal yields. The mismatch between required yields and available yields in risk-adjusted assets becomes a central policy and market concern.

From a broader standpoint, the pursuit of growth in such an environment becomes a delicate balancing act. On one hand, policymakers argue that low rates stimulate investment and spending by households and firms. On the other hand, the reality of negative real returns for savers and the challenge of funding long-term obligations raises questions about the sustainability of the current monetary and fiscal path. The evidence suggests that the low-rate regime, while intended as a stimulus, can function as a drag on the very savers whose behavior policy aims to influence. The result is a paradox where the policy intent (to promote growth through easier credit conditions) may run counter to the financial needs of households, retirees, and institutions that rely on steady, real returns to preserve and grow capital over time.

To put these dynamics in a broader economic frame, several related numbers reinforce the underlying risk. The average interest rate on U.S. debt remains modest at roughly 1.38%, even in a climate of low rates. Yet, the debt stock continues to grow and absorb a significant portion of fiscal capacity. Even with historically low rates, the Treasury has annual interest obligations running into hundreds of billions of dollars, underscoring how sensitive the fiscal position remains to shifts in rates. If interest rates were to rise to align with or exceed the inflation rate, the annual cost of servicing debt could escalate dramatically. For instance, if rates rise to match elevated inflation levels, the annual interest bill could rise by hundreds of billions to well over a trillion dollars, changing the trajectory of government spending and, potentially, program funding.

The debt landscape adds another layer of complexity. Since the Great Financial Crisis, the U.S. debt has surged from roughly $10 trillion to about $28 trillion. During the same period, GDP expanded from around $14 trillion in 2009 to roughly $21.4 trillion today, indicating that debt growth has outpaced nominal GDP growth by a wide margin. In other words, the accumulation of debt has outstripped the growth of the economy itself, raising questions about the sustainability of the current debt dynamics and the capacity of the economy to absorb new obligations without triggering sharper financial pressures.

Another critical factor in this equation is the Fed’s balance sheet, which expanded to more than $8 trillion in the aftermath of the Great Recession and has remained elevated for over a decade. The rationale offered by policymakers has been that asset purchases and balance-sheet expansion would alleviate financial conditions, support credit creation, and facilitate a recovery. Critics argue that such expansion has contributed to distortions in asset prices, reduced the relative attractiveness of traditional savings, and exposed the economy to the risks of a sudden retrenchment or a sudden shift in expectations about future policy.

The size and scope of the global Treasury market—estimated at over $128 trillion—adds another layer of market sensitivity. In such a vast market, the behavior of buyers and sellers is shaped not only by domestic policy but by a wide array of international considerations, including currency valuations, hedging needs, and cross-border capital flows. The fundamental question becomes whether market participants can be compelled to buy assets that yield negative real returns, especially in environments where alternative assets might offer competing risk-adjusted returns or where inflation remains a persistent, higher-than-target force.

Beyond the macro indicators, there is a widely cited valuation measure from the St. Louis Fed—the Warren Buffett Indicator. This metric compares the total value of all publicly traded stocks to the nation’s GDP, providing a snapshot of market valuation relative to the size of the economy. By several historical gauges, the Buffett Indicator signals that equity valuations are at elevated levels, with the current reading approaching or surpassing levels seen at prior peak periods. In the historical context, this valuation stance appears particularly stretched when juxtaposed with the dot-com era peak, when markets were vulnerable to abrupt corrections. The memory of the dot-com bust, including the dramatic drawdowns in names like Amazon during its early milestones, underscores the potential for significant volatility when valuations detach from underlying fundamentals.

The debt and governance narrative is inseparable from the GDP trajectory and the broader macroeconomic framework. Since the crisis, the debt component has grown much faster than the economy itself in nominal terms, with debt expanding roughly 2.5 times faster than GDP. This gap signals a growing intertemporal burden: current policy choices, if sustained, may reduce fiscal space and constrain future policy options whenever debt servicing becomes a larger share of government outlays. The juxtaposition of high debt, rising valuations, and negative real returns creates a complex decision environment for investors: follow price trends, monitor macro fundamentals, and weigh the risks of a policy shock that could abruptly alter the cost of capital and the value of assets.

In this environment, the central takeaway from these north-star metrics is that markets do not reward static thinking or rigid doctrines. Savers and investors alike confront an environment where the policies intended to promote growth may inadvertently discourage saving and legitimate capital formation. Traders who rely on price signals and trend-following techniques may find value in systems that can adapt to changing dynamics, while the broader economy contends with structural headwinds that demand disciplined risk management. Artificial intelligence, in this framing, becomes a tool to identify, quantify, and respond to evolving patterns in real time, helping market participants navigate a landscape defined by high debt, shifting policy, and volatile valuations.

As for the long-term perspective, the key observation remains: price trends and risk dynamics tend to dominate over mere opinions or theoretical forecasts. A chart-based approach to the Treasury market—watching for support or resistance levels and the potential for sharp moves if a macro regime changes—becomes critical in assessing where capital may flow next. The notion that the “trend is the truth” gains traction when confronted with a world where policy levers can abruptly alter the calculus of risk and return. In such a sense, the real story is less about a single forecast and more about how markets price, re-price, and absorb information across a broad spectrum of asset classes, from government bonds to equities, from cash-like safeties to alternative strategies that may hedge against negative real yields.

This section has laid out the core data points and the logical threads connecting them: a negative real rate backdrop, high absolute debt levels relative to GDP, evolving federal fiscal commitments, and a market that looks expensive by several traditional yardsticks. The following sections will expand on the practical implications for savers and pension funds, explore the debt service dynamics and Federal Reserve policy choices, examine market valuations in relation to GDP, and discuss how traders might navigate a world where AI and data-driven decision making are increasingly central to success.

The Implications for Savers and Pension Funds

The negative real rate environment described above has direct consequences for households, retirees, and institutions charged with safeguarding long-term financial security. When nominal returns on safe assets lag behind inflation, the purchasing power of savings erodes over time. For households, this erosion translates into slower accumulation of wealth, reduced capacity for future spending, and heightened vulnerability to unexpected expenses or shocks. For retirees and near-retirees, the pressure is even more acute: the income streams needed to sustain living standards in retirement depend heavily on a predictable sequence of returns from savings, pensions, and other investments. If the real return on core savings instruments is negative, retirees may need to adjust retirement ages, savings rates, or anticipated standards of living to accommodate the reality of diminished purchasing power.

Pension funds, which shoulder the obligation of providing retirement benefits to a broad base of workers, are particularly sensitive to the dividend of real returns. The traditional expectation of a 7% yield as a benchmark for pension fund viability rests on the assumption that investment income, dividends, and capital gains will keep pace with or exceed the growth of liabilities. When government bonds—often a central component of many pension portfolios—offer negative or barely positive real returns, the ability of pension funds to meet obligations can come under strain. This is especially pressing in an environment where actuarial assumptions underwrite long-dated liabilities that extend decades into the future, and where demographic shifts place increasing stress on funding ratios. The mismatch between the need for durable, reliable returns and the constraints imposed by low nominal yields on safe assets contributes to a broader concern about the sustainability of pension financing under current monetary conditions.

The broader savings landscape also faces a calculus of opportunity cost. Hundreds of billions of dollars, and in some scenarios trillions when scaled to longer horizons and broader asset classes, are allocated to fixed-income securities with real returns that are negative in the face of persistent inflation. Savers seeking to maintain or grow purchasing power must consider alternative asset classes that may offer better hedges against inflation or longer-term capital appreciation. Those alternatives include equities with earnings growth prospects, real assets, inflation-linked securities, and diversified investment approaches that balance risk and return. However, these options come with their own risk profiles, liquidity considerations, and correlations across market regimes. The central theme remains: in an environment of sustained negative real yields, prudence, diversification, and time horizon management become essential.

There is, therefore, a crucial tension to recognize: the traditional safety of “risk-free” assets may no longer deliver an adequate buffer against inflation for many households and institutions. This reality pushes investors toward a broader set of risk-aware strategies, a framework for evaluating tradeoffs, and a disciplined approach to capital preservation that still seeks opportunities for growth. In practical terms, households may reassess how they allocate savings across cash, insured deposits, government bonds, and alternative investments. Individuals planning for retirement might re-evaluate their projected retirement date, savings rate, and the level of risk in their portfolios, seeking a balance between capital protection and growth that aligns with a more uncertain real-return landscape.

The policy dimension interacts with savers and pension funds in meaningful ways. If central banks remain constrained by the need to diversify the sources of liquidity and maintain broader financial stability, there could be an implied limit on how aggressively they can normalize policy to reduce the drag of negative real returns. In such a regime, savers may experience a gradual secular shift toward a wider set of financial instruments and an increased emphasis on risk management, liquidity planning, and the use of hedges against inflation and interest-rate changes. This shift would affect how households build emergency funds, how pension boards calibrate asset allocations, and how financial intermediaries design products that address the needs of a population living in a world of persistent price increases but constrained nominal gains.

From a practical standpoint, households should consider the following priority actions in light of negative real returns and the current debt dynamics:

- Reassess emergency fund liquidity to ensure it remains accessible and does not erode in real terms during inflationary periods.

- Explore inflation-protected or inflation-sensitive assets that can better maintain purchasing power over time.

- Review long-term financial plans, including retirement projections, to reflect the reality that nominal returns may lag inflation for an extended period.

- Emphasize diversification to manage risk and identify assets with reasonable prospects for capital appreciation in different macro regimes.

- Use disciplined contribution strategies, such as automatic increases in savings rates, to offset erosion and maintain a trajectory toward financial goals.

Another dimension to consider is the potential role of policy adjustments and structural reforms in shaping savers’ outcomes. If policy makers respond with measures that gradually improve the real return landscape—through targeted inflation stabilization, better management of debt service costs, or more remunerative long-term investment options for savers—the environment for households and pension funds could gradually become more favorable. Conversely, if debt accumulation continues to outpace growth without commensurate gains in productivity or inflation containment, savers may face a prolonged period of headwinds. The implications for public policy, corporate strategy, and individual financial planning are therefore interconnected and far-reaching.

A critical point to internalize is the conditionality of outcomes around expectations and policy choices. The negative real return signal is not simply a theoretical construct; it translates into a set of practical considerations for how households and institutions allocate capital, how pension funds meet obligations, and how traders think about risk and opportunity in a world where the ratio of yield to inflation is unfavorably skewed toward the inflation side. In such a framework, the quality of information, the speed of analysis, and the ability to adapt to shifting conditions become essential skills for investors and policy participants alike.

As the discussion of savers and pension funds unfolds, it is important to connect these realities to the broader market and macroeconomic picture. A sustained negative real return environment has implications for the demand curve for various assets, including government bonds, corporate debt, equities, real assets, and innovative financial instruments. It may also shape the risk appetite of markets, influencing how much risk investors are willing to take in pursuit of enhanced returns, as well as how they price risk into asset valuations. The convergence of higher debt service costs, potential policy shifts, and evolving investor behavior creates a dynamic environment that rewards those who can synthesize data across macro indicators, pricing signals, and risk-reward tradeoffs with discipline and clarity.

In sum, the implications of negative real returns for savers and pension funds are wide-ranging and deeply consequential. They touch everyday financial security, the funding of retirement promises, and the structure of investment portfolios across households, institutions, and markets. The challenge is not simply to identify a problem but to translate that understanding into prudent actions, careful risk management, and a readiness to adjust plans as the macro landscape evolves. The next section delves into the debt service dynamics and the policy choices faced by the Federal Reserve and the government, revealing how these forces interact with savers’ outcomes and market behavior.

The Debt, Interest Costs, and the Fed’s Balancing Act

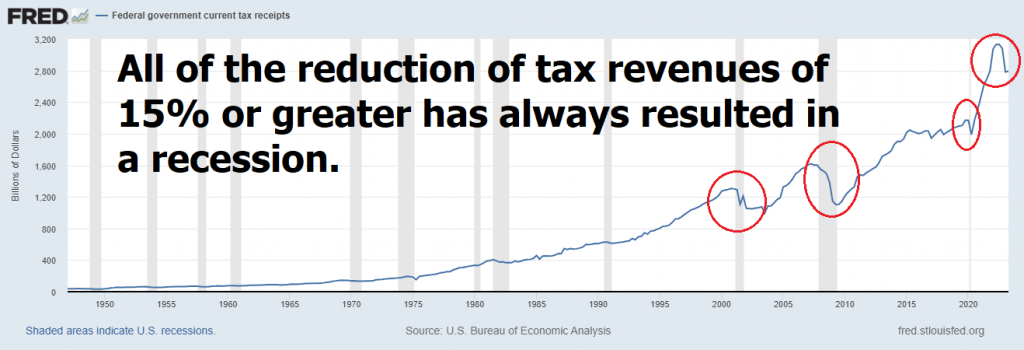

A central dynamic in this era is the relationship between debt accumulation, the cost of servicing that debt, and the policy choices available to the central bank and the government. The current interest-rate environment, the maturity profile of sovereign debt, and the size of the government’s balance sheet together shape the contours of fiscal sustainability and financial stability. Several interlocking facts frame the discussion:

-

The U.S. debt stock has risen dramatically since the Great Financial Crisis, moving from roughly $10 trillion to around $28 trillion. This expansion reflects persistent fiscal deficits, as well as the use of debt instruments to finance emergency measures, stimulus programs, and ongoing public spending.

-

Despite the large debt stock, the average rate on federal debt remains relatively modest, at approximately 1.38%. This low rate provides fiscal space by reducing annual interest obligations relative to the debt level. However, even at these low rates, the absolute cost of servicing the debt is substantial due to the scale of the debt.

-

The economy’s current GDP stands around $21.4 trillion, up from about $14 trillion in 2009. Although GDP has grown, the debt level has grown by more than the economy, implying that debt increasingly weighs on the fiscal trajectory. Debt growth outpacing GDP by a wide margin signals longer-run vulnerabilities if growth slows or if rates rise.

-

The interest expense associated with the debt remains a critical line item for the Treasury. Even at today’s low yields, the interest payments total hundreds of billions of dollars per year. If interest rates were to rise to reflect higher inflation or to normalize toward longer-run targets, these payments could escalate sharply. Some projections suggest that if rates rose enough to align with published inflation figures or beyond, annual interest outlays could surge to over $1.2 trillion, altering the scale of government budgeting and potentially affecting other programs and priorities.

-

More than half of the U.S. sovereign debt is scheduled to mature within the next three years. This high concentration of near-term maturities creates refinancing risk and exposes the government to sensitivity to rate changes. The ability to roll debt cheaply hinges on the prevailing interest-rate environment. If rates move higher, the cost of rolling over maturing debt could rise quickly and require either higher taxes, more borrowing, or reductions in spending.

-

The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet expansion to roughly $8 trillion since the 2008 crisis is an essential backdrop to the policy debate. The central bank’s purchases of Treasuries and other assets were designed to stabilize markets and support growth during a period of economic weakness. The policy stance faced by the Fed today is complicated by the potential consequences of higher rates or a reduction in purchases on the Treasury market and on the broader economy. A tightening path, if pursued aggressively, could elevate debt-servicing costs and slow growth, while a more accommodative path could leave inflation pressure unaddressed or distort asset valuations.

-

The balance between monetary and fiscal policy determines how the economy absorbs debt and sustains demand. If the Fed continues to purchase securities or maintains a very accommodative stance, it can support liquidity and lower the cost of borrowing in the short term. However, if the Fed touches a tapering path or reduces asset purchases, it signals a shift toward a tighter financial condition, potentially raising rates and increasing the cost of debt servicing. The dynamic is delicate: the market’s perception of future policy can move capital flows, impact the value of Treasuries, and influence the pricing of other assets across a wide spectrum.

-

The global Treasury market magnitude matters because a substantial portion of government debt is financed in a global context. With a market size of around $128 trillion, the Treasury market is deeply interconnected with foreign exchange dynamics, cross-border investment flows, and international risk sentiment. Traders, investors, and institutions around the world participate in this market, and policy shifts in the United States have spillover effects that extend beyond domestic borders. The scale of this market means that any abrupt policy change or major shift in expectations can produce rapid changes in prices and volatility.

An important analytical takeaway from this debt-and-policy framework is the notion that the Fed’s ability to “control” the economy through rate changes and asset purchases has become constrained by the debt load and the need to avoid triggering a debt-service shock. The metaphor often used on Wall Street, “pushing on a string,” captures the idea that monetary policy may be effective in directing government spending but cannot compel households or businesses to spend if they choose not to. When the private sector opts out of spending, the policy transmission to growth weakens, limiting the effectiveness of even aggressive policy actions.

Since the onset of the Great Financial Crisis, the central bank’s expanded balance sheet has been a tool of stabilization, but it also raises questions about long-run normalization. If the Fed lowers rates further, it becomes the sole buyer of Treasuries, reinforcing a dependency that could complicate any future normalization. If tapering is pursued, it sends a signal that government spending may need to be reduced or financed differently, potentially impacting fiscal programs and the broader economy. If rates rise, the Treasury must allocate more to interest payments, potentially squeezing other areas of the budget.

The debt-and-policy picture has real consequences for market participants. A treasury market facing the prospect of higher rates, heavier refinancing needs, and shifting demand dynamics can be subject to significant volatility. Investors must consider the risk that the cost of debt service will mount, and the price of Treasuries could move in unexpected ways as expectations adjust to evolving policy frameworks. The broader implication for traders is that core macro relationships—debt load, rate trajectory, inflation expectations—are in flux, demanding robust risk management, diversified strategies, and a willingness to adapt to changing conditions.

A particularly salient point is the potential for policy misalignment or miscalibration to create sudden financial stress. If policymakers perceive that higher rates would lead to a default-like scenario for the Treasury or undermine the ability to fund essential services, there could be political and market consequences. The risk is not only about the magnitude of debt but also about the confidence that market participants place in the government’s ability to meet obligations and sustain growth. This is why the debt dynamics, in combination with inflation and the policy toolkit, occupy a central role in any comprehensive assessment of the economic outlook and the investing landscape.

Looking ahead, the alignment (or misalignment) between debt service costs, inflation trajectories, and policy choices will shape the viability of different asset classes. For traders and investors, this means monitoring a range of indicators—debt maturity profiles, official inflation data, the trajectory of the Fed’s balance sheet and asset purchases, and the pricing signals in the Treasury and derivative markets. The goal is to identify when the market is pricing in a shift in fundamentals that could alter expectations about risk, return, and capital allocation. As the debt picture evolves, the scope for policy-driven relief or risk build-up will depend on how credible and sustainable the fiscal and monetary paths prove to be.

The Fed’s strategic challenge, in short, is to navigate a world where debt is heavy, rates are low by historical standards, and the need to maintain confidence in the currency remains paramount. Balancing these pressures requires careful communication, disciplined policy choices, and a readiness to adjust as new data emerge. The interaction between debt, inflation, and monetary policy will continue to be a dominant driver of asset prices, investor sentiment, and the broader economic narrative in the years ahead. The next section analyzes how market valuations relate to national income and why one widely watched gauge—The Warren Buffett Indicator—has become a focal point for assessing whether equities are pricing in too much optimism relative to economic output.

Market Valuation Signals: The Warren Buffett Indicator and Stock vs GDP

Valuation is a central facet of investment decision-making, and one widely cited framework for evaluating market levels is the Buffett Indicator. Named after Warren Buffett, this indicator uses a simple ratio: the total market value of all publicly traded stocks divided by the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). The logic is straightforward: if stock prices price in a level of corporate earnings and growth that dwarfs the size of the economy, valuations may be stretched, signaling potential vulnerability to a correction should earnings growth disappoint or macro conditions deteriorate.

The current reading on the Buffett Indicator is striking: the stock market, when measured against the nation’s GDP, sits at roughly twice the level seen during the dot-com bubble era. The dot-com bust of 2000 stands as a cautionary historical example, where once high-flying tech stocks collapsed, and even well-known names saw dramatic declines. The referenced reference to Amazon’s sell-off of more than 85% during that period serves as a reminder that high valuations can reverse sharply when the growth narrative falters, liquidity tightens, or earnings disappoint. The takeaway for investors is not to dismiss historical context but to consider whether current stock prices reflect sustainable earnings, productivity gains, and real improvements in the economy or whether they have risen largely on multiple expansion and liquidity-driven demand.

The Buffett Indicator has consistently indicated elevated valuations in this cycle, prompting questions about the sustainability of profits, dividends, and share repurchases given the macro backdrop of debt, inflation, and policy constraints. It is important to recognize that no single indicator can perfectly predict the timing of a market peak or the duration of a bull phase. Yet, when multiple valuation signals converge on an elevated level, concerns about the possibility of a mean-reversion event gain salience. Investors often use such signals to calibrate their risk exposures, adjust portfolio allocations, and consider hedging strategies that might mitigate the downside risk associated with a potential correction.

Beyond the Buffett Indicator, the broader debt-to-GDP narrative reinforces caution about the sustainability of high equity valuations. Since the crisis, the U.S. debt has grown from $10 trillion to nearly $28 trillion, while GDP rose from approximately $14 trillion in 2009 to $21.4 trillion in more recent years. The growth of debt has outpaced GDP by a factor of more than two, signaling structural headwinds for the economy. In this frame, equity valuations can be seen as capturing not only earnings prospects but also the market’s expectations about how the economy will grow under debt constraints, and how inflation, rates, and policy will shape corporate profitability and investment.

There is a broader principle at work: markets tend to price in expectations about growth, inflation, and policy, and those expectations can become self-fulfilling to some extent. If valuations become stretched, the risk of a correction grows as investors reassess their assumptions about the durability of earnings, the path of interest rates, and the sustainability of debt trajectories. Conversely, if investors perceive a prolonged period of policy accommodation and low real rates with supportive liquidity, valuations may remain elevated for an extended period. The complex mix of macro signals, policy actions, and investor sentiment makes it essential to monitor multiple indicators in tandem rather than relying on a single metric in isolation.

In this context, the call to “follow the price” has practical implications for trading and investing. Price movements reflect the market’s synthesis of a wide array of information and expectations. When prices move in a way that appears to be misaligned with fundamentals, it signals potential opportunities for those who can identify enduring drivers and manage risk. However, in an environment where debt, inflation, and policy shifts interact in unpredictable ways, a disciplined approach to trend analysis, risk management, and data-driven decision making becomes essential. The emergence of AI-driven tools can support traders by processing large data sets, recognizing patterns, and testing scenarios that human analysis might overlook.

The valuation narrative must be paired with the GDP and debt dynamics to understand the full picture. High stock valuations in the context of rising debt and complex policy choices imply that a negative regime risk factor may be rising. While a robust earnings environment can justify higher valuations, the sustainability of such earnings depends on macro stability, productivity growth, and the capacity of the economy to absorb debt without triggering a sharp rise in rates or inflation. Investors should weigh the probability of earnings resilience against the risk that policy changes, debt service burdens, and inflation dynamics could erode margins or growth trajectories.

The macro-to-market linkage discussed here also has implications for asset allocation. If the Buffett Indicator and related measures indicate stretched equity valuations, investors may consider hedged or diversified strategies, drawdowns in risk exposures, or a tilt toward quality names, stronger balance sheets, and secular growth themes that may better withstand macro volatility. Conversely, if valuation signals show potential for further upside driven by earnings growth, innovation, or policy-driven demand, investors may maintain or adjust exposures accordingly while remaining mindful of risk.

In sum, the valuation landscape—as captured by the Buffett Indicator, debt dynamics, and inflation-rate interactions—tells a story of elevated market levels against a backdrop of structural challenges. The risk of mispricing exists, and the potential for price corrections remains, especially if macro surprises emerge or if policy actions shift in ways that significantly alter the cost of capital. Traders and investors who stay attuned to the interconnections among debt, rates, inflation, and earnings can position themselves to navigate volatility and discern opportunities that align with the evolving macro regime. The next section examines how monetary policy dynamics—tapering, rate adjustments, and the global debt puzzle—shape this environment and what those actions imply for market risk and potential reward.

Monetary Policy Dynamics: Tapering, Rates, and the Global Debt Puzzle

At the heart of the policy environment is a tension between the actions needed to curb inflation, the risks posed by a high debt burden, and the unintended consequences that may accompany policy changes. The Fed’s toolkit—interest-rate adjustments, asset purchases, and balance-sheet policies—functions as the primary mechanism by which monetary conditions are shaped. The key policy trade-offs revolve around three interconnected channels: how rate changes influence borrowing costs and investment, how asset purchases influence liquidity and risk premia, and how tapering or policy normalization signals future fiscal paths for the government.

First, lowering interest rates and maintaining accommodative monetary conditions can stimulate borrowing and spending, potentially supporting growth and helping to avert a credit tightening spiral. However, such a policy stance may exacerbate the erosion of savers’ real returns, contributing to a further widening between nominal income on safe assets and inflation. The real consequence for savers and pension funds is that, even as the federal government borrows at historically low rates, the cost to households and institutions for maintaining liquidity and capital preservation remains high in real terms. The balance needed is delicate: supportive policy is prudent when growth momentum is weak, but it risks fueling asset-price inflation or mispricing risk if kept too long.

Second, the Fed’s asset purchases and balance-sheet expansion have effectively provided a backstop for the Treasury market, stabilizing prices and providing liquidity when markets have faced stress. If the Fed continues to purchase Treasuries, it maintains a cushion for the debt markets and reduces the probability of abrupt losses in price or liquidity. Yet there is a critical consideration: such purchases can perpetuate a situation where the market’s sensitivity to monetary tightening grows, because investors come to rely on central-bank support. The complexity of unwinding a multi-trillion-dollar balance sheet poses potential challenges, including the risk that tapering could raise long-term rates and disrupt markets if not managed smoothly.

Third, if policymakers opt to raise rates to counter inflation, the costs of debt servicing rise in proportion to the size of the debt and the maturity structure. The near-term implication is higher interest expenses for the Treasury, which could crowd out discretionary spending and place additional pressure on the fiscal budget. For markets, a credible and well-communicated path toward rate normalization could eventually reduce the risk premium embedded in long-duration assets, but the transition may be accompanied by higher volatility as investors reassess longer-term risk and return. The trade-off is whether higher rates can be absorbed without triggering a destabilizing shift in borrowing costs or a debt service shock that undermines confidence in the fiscal trajectory.

Fourth, the size of the global debt market and the interconnections between the U.S. monetary stance and international capital flows add further complexity. The global Treasury market’s enormous scale means that policy shifts in the United States have spillovers across currencies, cross-border investment, and risk appetite around the world. The possibility that negative-yield or low-yield environments could prompt “dash outs” from fixed-income instruments creates a dynamic where currency valuations and cross-asset correlations can bend in response to policy signals. The risk remains that ill-timed policy moves could trigger abrupt shifts in global capital flows, with implications for both financial markets and the real economy.

Fifth, the policy-currency dynamic intersects with structural considerations in the economy, including the potential for “new tools” and data-driven approaches to help investors identify trends amidst volatility. The development of advanced analytics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence offers a set of capabilities for processing vast datasets, detecting patterns, and evaluating risk-reward tradeoffs across multiple asset classes and regimes. For traders, these tools can help improve timing, risk controls, and the identification of robust, repeatable market signals. However, such technology also introduces new risks, including model risk, data dependence, and the need for transparent and auditable decision frameworks.

A critical macro question is whether the policy toolkit can be calibrated to achieve both inflation stabilization and debt sustainability without triggering unintended consequences elsewhere in the economy. The tension between stimulating growth and maintaining financial stability is not resolved solely by demonstrating that policy tools work in theory; it requires careful examination of transmission mechanisms, the behavior of borrowers and lenders, and the evolving structure of global finance. The conversation about tapering, rate normalization, and balance-sheet normalization continues to unfold as data arrive, inflation dynamics shift, and financial markets adjust to new expectations about the path ahead.

As this discussion moves forward, the practical implications for market participants center on risk management and the preparation for potential volatility. Traders should be prepared for a range of scenarios, including gradual normalization, delayed normalization, or even sudden reassessment of inflation and growth trajectories. This implies maintaining robust risk controls, diversifying across asset classes, and leveraging data-driven insights to navigate the shifting policy and market landscape. The persistent debt burden, coupled with the complexity of monetary policy, suggests that market participants should adopt a flexible stance that accommodates evolving macro conditions, while remain mindful of the potential for outsized moves in response to new information.

The final section of this analysis turns to the frontier of trading strategy in this environment: the role of artificial intelligence in trend identification, decision making, and risk management. The aim is to understand how advanced analytical tools can complement human judgment to deliver a disciplined approach to investing in a world characterized by high debt, inflation pressures, and policy uncertainty. The discussion also addresses the critical caveat common to all trading activity: the substantial risk of loss, and the imperative to use risk capital prudently. While AI can offer powerful capabilities, it does not eliminate risk; it must be deployed with careful governance, skepticism, and continuous validation of performance.

The New Frontiers in Trading: Artificial Intelligence, Trends, and Risk Management

In this section, the narrative shifts toward the practical implications of using advanced analytics and artificial intelligence to identify market trends, manage risk, and improve decision making in a complex macro environment. The core proposition is that AI-enabled tools can process vast streams of data, recognize patterns across equities, bonds, currencies, and commodities, and generate timely, data-driven insights that help traders act more decisively in the face of uncertainty. The promise is not that AI will replace human judgment, but that it can augment it by offering robust trend detection, scenario analysis, and probabilistic assessments that account for multiple possible futures.

To appreciate how AI can contribute to trading success, it is helpful to consider a few fundamental principles that underlie effective trend-following and risk management:

-

Trend following hinges on the persistence of price movements over time. When a market exhibits a clear directional move, AI models can help quantify the strength and durability of that trend, distinguishing enduring dynamics from short-lived noise. By tracking moving averages, momentum indicators, volatility regimes, and correlations across asset classes, AI can help traders time entries and exits with greater consistency.

-

Risk management is the fulcrum of any trading strategy. AI-driven systems can continuously monitor portfolio risk metrics, including drawdown risk, value-at-risk, and conditional drawdown, and adjust exposures to keep risk within predefined bounds. Dynamic risk control becomes particularly important in periods of heightened volatility and regime shifts, where traditional, static risk measures may underestimate potential losses.

-

Data diversity and processing power enable more sophisticated scenario analysis. AI models can simulate a broad range of macro scenarios, incorporating changes in inflation, interest rates, growth, and policy actions. This capability helps traders evaluate the resilience of their strategies under various contingencies, supporting more resilient decision-making during market stress.

-

Adaptive learning allows AI systems to refine their signals as new information arrives. While this adaptability can improve responsiveness, it also introduces the risk that models overfit to recent patterns or become unstable during regime changes. Robust governance, backtesting, out-of-sample validation, and monitoring are essential to ensuring that AI-driven strategies remain robust and transparent.

-

The human element remains indispensable. AI can provide a richer, data-driven basis for decisions, but it cannot substitute for disciplined risk management, clear objectives, and a well-structured trading plan. Successful traders use AI as a complement to their experience, judgment, and an explicit understanding of their risk tolerance and time horizon.

In the current environment, AI-assisted trading could support several practical use cases:

-

Trend discovery across multiple asset classes to identify long-running momentum or mean-reversion opportunities that would otherwise be obscured by noise.

-

Dynamic allocation decisions that adjust exposure to stocks, bonds, and alternative assets based on evolving risk premia and macro signals.

-

Volatility management through adaptive hedging and options strategies that respond to changes in implied and realized volatility.

-

Stress testing and scenario analysis that help traders anticipate how portfolios might respond to extreme but plausible events, such as a sudden shift in inflation expectations, a rapid change in policy stance, or a regime shift in liquidity.

-

Risk budgeting that ensures capital is allocated to strategies with complementary risk profiles, reducing drawdown across market cycles.

As with any trading approach, there are essential caveats and safety considerations. The performance of AI-driven systems depends on the quality of data, the validity of assumptions, and the ongoing supervision of models. Real-world results can diverge from back-tested results, and performance can be sensitive to structural changes in the market, such as drastic policy shifts or unprecedented volatility episodes. It is critical to implement rigorous risk controls, including diversification, position sizing, and stop-loss rules, to prevent outsized losses during periods of regime change. In addition, ethical and regulatory considerations should inform the deployment of AI in trading, ensuring transparency, accountability, and compliance with applicable rules.

The literature on AI in trading also emphasizes the importance of a disciplined process for model development and deployment. This includes establishing clear performance metrics, regular audits of model behavior, and an emphasis on robust risk management rather than pursuing aggressive returns at any cost. While AI can enhance decision making and enable faster reaction times, it does not guarantee profits and cannot overcome structural market risks. The most successful outcomes arise from the thoughtful integration of AI insights into a well-structured investment framework that combines empirical validation, prudent risk controls, and a long-term perspective.

Readers are reminded of the fundamental risk disclosures that accompany trading and investing. The complexity of financial markets and the potential for significant losses means that only risk capital should be used for trading activities. Any engagement with stocks, futures, options, currencies, and other financial instruments involves substantive risk, and past performance is not indicative of future results. It is essential to approach trading with humility, discipline, and a reliance on tested processes rather than speculative bets. While AI can illuminate patterns and reduce noise, it does not eliminate the possibility of loss, and prudent risk management remains non-negotiable.

In practice, the integration of AI into trading strategies should be undertaken with a clear plan, explicit risk controls, and an ongoing commitment to evaluating performance across market regimes. Traders who can combine the speed and breadth of AI analysis with human judgment and a disciplined framework are more likely to navigate volatility and identify durable opportunities. The path forward involves balancing innovation with caution, embracing data-driven insights while preserving a grounded understanding of macro fundamentals, and maintaining a commitment to risk management that protects capital across cycles.

This discussion foregrounds a broader idea: in a Brave New Financial World characterized by structural shifts in debt, inflation, and policy, new analytic tools and data-driven approaches will be central to investment decision making. The objective is not to chase every trend but to identify robust, high-probability opportunities that align with a trader’s risk tolerance and time horizon. Whether markets are in a risk-on or risk-off regime, the disciplined use of AI-assisted trend detection and risk management can become a differentiator for capable traders who stay focused on process, not just outcomes.

Important risk disclosures and performance caveats accompany every trading activity. There is a substantial risk of loss associated with trading, and only risk capital should be used. Trading stocks, futures, options, forex, and ETFs involves significant potential rewards but also significant potential risk. The information presented herein does not constitute solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any financial instrument. Past performance of any trading system or methodology is not necessarily indicative of future results. No representation is being made that any account will achieve profits or losses similar to those discussed. The legal and regulatory disclaimers that apply to trading are essential and should be reviewed carefully by any potential participant. The guidance here focuses on understanding macro relationships, recognizing price-driven opportunities, and employing disciplined risk management as the foundation for trading in an environment of high debt, inflation, and policy flux.

Conclusion

Trust and clarity in the face of global economic turbulence hinge on translating complex data into actionable understanding. This analysis has surveyed the core signals—the 10-year Treasury yield, official inflation, and the resulting real rate of return—as well as the debt trajectory, the cost of servicing that debt, and the policy tools available to the central bank and government. The negative real-rate regime, the substantial debt burden, and the valuation backdrop for equities all point to a fragile balance where savers’ purchasing power is under pressure and market dynamics are sensitive to policy shifts. Pension funds and households face increasingly difficult tradeoffs as they seek to protect capital while still pursuing growth.

The broader macro picture—debt growth outpacing GDP, a large share of near-term debt maturities, and a global Treasury market of immense size—intensifies the need for prudent risk management, disciplined investment decisions, and a flexible approach to asset allocation. The Buffett Indicator and related valuation metrics suggest that equity valuations are elevated relative to output, reinforcing the caution that mean reversion could occur if earnings, inflation, or policy paths surprise investors.

Monetary policy dynamics—rate adjustments, tapering, and balance-sheet normalization—will continue to shape the cost and availability of credit, the pricing of risk, and the trajectory of asset prices. Each policy choice carries trade-offs: stimulating growth and preserving liquidity versus risking higher debt service costs and asset price distortions. In this environment, traders and investors can benefit from embracing data-driven methodologies, including AI-assisted trend analysis, to identify durable patterns and manage risk effectively. Yet, the ultimate safeguard remains prudent risk management, diversified exposure, and an adaptable strategy that acknowledges the potential for rapid regime shifts.

As the financial system evolves, the intersection of macro fundamentals, market valuations, and policy decisions will determine how capital flows and how risk is priced. The opportunity resides in recognizing and responding to shifts, rather than clinging to oversimplified conclusions. A disciplined approach—rooted in price signals, robust risk controls, and a thoughtful integration of technology with human judgment—offers the best path to navigating a complex, dynamic financial landscape. The road ahead may be volatile, but it also holds opportunities for those who remain attentive, methodical, and resilient in the face of change.