We are now roughly six weeks into the federal government’s fiscal year 2024, and if last year’s tempo is any guide, Americans should brace for a turbulent ride. Washington’s debt trajectory continues to climb at an astonishing pace, casting a long shadow over the nation’s fiscal health. The September Monthly Treasury report highlighted a striking development: the United States added about $1.7 trillion in debt for the 2023 fiscal year, which concluded on October 31. That figure represents a substantial 23 percent rise from 2022, or about $319 billion more in borrowing. The sheer scale of that increase underscores the ongoing and mounting fiscal pressures facing the government as it finances a wide range of programs, subsidies, and operations at a time when revenue streams are under scrutiny and investment markets are watching carefully.

However, a chorus of mainstream analysts urges caution in interpreting that $1.7 trillion headline. Critics contend that the Treasury Department may have counted a windfall from the cancellation of the student loan forgiveness program as federal revenue, a treatment that reduces the apparent deficit by roughly $300 billion. If that accounting choice is removed, the underlying deficit appears much larger—closer to doubling from 2022 to 2023, rising from roughly $1 trillion to around $2 trillion. In other words, the official narrative of a modest 23 percent increase may obscure a far more abrupt and dramatic expansion in the government’s net borrowing. This perspective invites a deeper examination of the true pace of debt accumulation and the sustainability of fiscal policy in an environment of elevated deficits and higher interest costs.

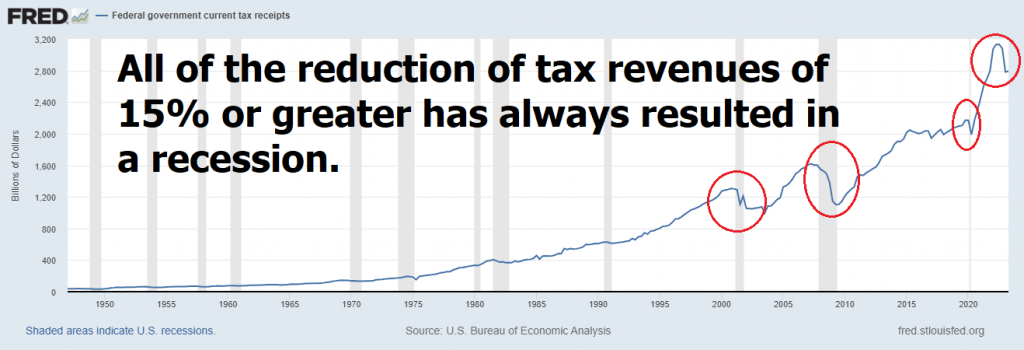

A foundational concern emerges from the heart of the policy debate: if the economy is as robust as authorities insist, tax receipts should rise in tandem with growth. Yet a chart from the St. Louis Federal Reserve provides a stark counterpoint. The data suggest that when the government experiences tax revenue declines of 15 percent or more, the economy tends to slip into recession or worse. The implication is clear: tax receipts are not immune to the health of the private sector; they decline when businesses struggle to generate profits, and the government’s revenue base, which includes income taxes, payroll taxes, corporate taxes, and a multitude of consumption and wealth taxes, suffers as a consequence. A comprehensive view of federal revenue highlights the breadth of sources: personal and corporate income taxes, payroll taxes funding social insurance, corporate taxes on profits, value-added or goods-and-services taxes on consumption, excise taxes on specific goods, customs duties and tariffs on imports and exports, estate taxes on inherited wealth, capital gains taxes on asset sales, and property taxes collected locally. When the private sector falters, the tax base shrinks, and federal revenue follows suit. A contrary view—one that claims tax receipts rise with a strong economy—fails to find support in the historical record whenever tax collections dip by a sizable margin and the economy remains vibrant.

To put these dynamics in sharper context, consider the broader fiscal backdrop. The deficit trajectory is steering the nation back toward the high-water mark seen during the 2020 and 2021 periods when the government deployed aggressive spending to sustain activity through the lockdowns. The cumulative effect of those deficits has pushed the national debt to the eye-popping level of nearly $34 trillion. That figure translates into more than $6 trillion added since the onset of the Covid crisis and about $18 trillion accumulated since the 2008 financial crisis. It is a staggering magnitude that continues to shape financial markets and policy debates alike. The scale also raises questions about the long-run implications for debt servicing, inflation, and the nation’s capacity to fund competing priorities without triggering adverse consequences for growth and stability.

As readers reflect on these numbers, it’s worth recalling the 2009 pledge associated with monetary accommodation. Former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke assured markets that the Fed would inject roughly $600 billion to add liquidity to the economy as a one-time measure. That commitment, delivered in a period of crisis, resonates through the current dialogue about balance sheet management and the risk of ongoing liquidity support, given the scale of today’s debt and the contemporaneous commitment to stabilize financial conditions. The historical context matters because it frames how policymakers and investors view the risk of continuing, large-scale intervention in credit markets and the broader financial system.

A separate but closely linked thread in this fiscal narrative is the evolution of the labor market and corporate headcount. In the current year, corporate announcements have revealed a swelling tally of job cuts—604,514 positions had been announced by mid-year—a staggering 198 percent increase relative to the 209,495 cuts reported through September 2022. This figure marks the most significant scale of reductions in the January-to-September period since the pandemic year of 2020, when the economy faced unprecedented disruptions. Excluding that extraordinary period, the 2024 tally stands as the highest since the wake of the 2008 financial crisis in 2009. The juxtaposition of accelerating job reductions with falling tax revenues and ballooning deficits adds a layer of tension to the narrative: how strong can the economy feel if unemployment is rising and the tax base is contracting?

This discussion cannot ignore the broader macroeconomic tensions surrounding finance, credit, and monetary policy. Despite the apparent severity of job-cut announcements, the economy is being described as resilient by policymakers and many market participants. A central feature of this debate is the ongoing discussion around yield curve control (YCC) and its potential implications for financial markets and economic functioning. YCC describes a framework in which central banks attempt to fix certain borrowing costs by buying or selling government bonds to hold them at targeted levels. Critics argue that this approach effectively mutes the free market dynamic, replacing price discovery with deliberate policy steering and potentially sowing the seeds for mispricing and misallocation of resources. The contention is that when the central bank sets the cost of money too low for too long, the result can be a loss of market discipline, a distortion of incentives, and unintended consequences for inflation and asset prices.

The debate around yield curve control has drawn parallels to the past, notably the World War II era when substantial debt and heavy government borrowing pressed the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve. Back then, the policy response included rate caps that ultimately contributed to a loss of control over the money supply and the central bank’s balance sheet. The comparison is often used to argue that once such tools are deployed, they become difficult to unwind, raising the specter of a path that departs from free-market principles toward a more centrally managed financial order. The argument advanced by critics is not that interest rates should be immune from policy consideration, but that a sustained period of interest-rate manipulation erodes the conditions under which markets allocate capital efficiently and can lead to a misalignment between the price of borrowing and the true state of the economy.

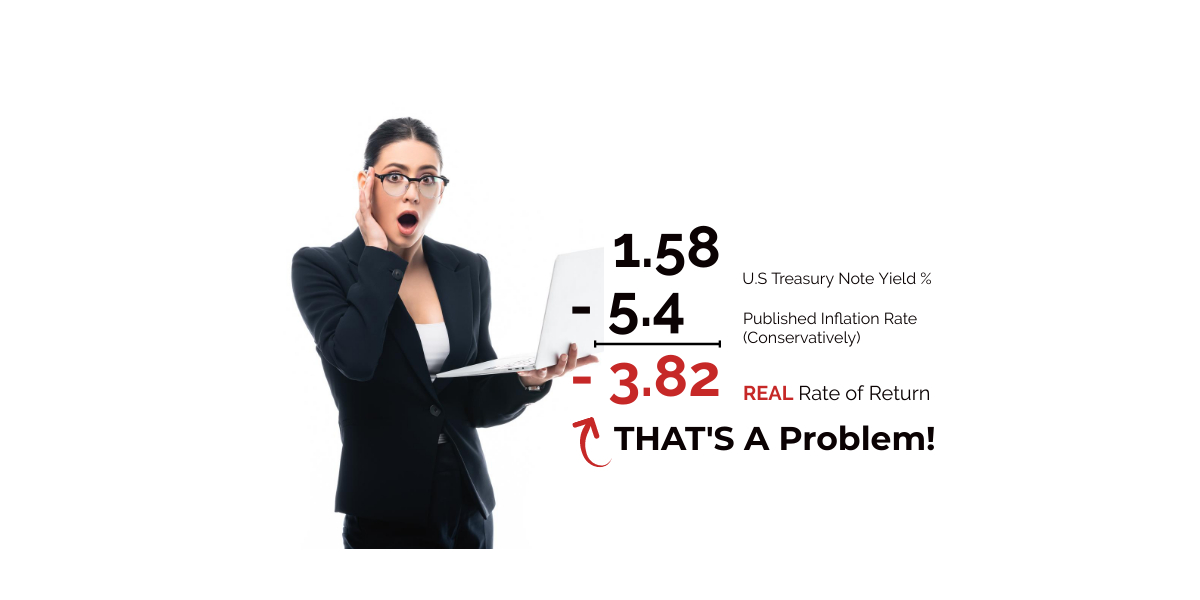

In this climate, the performance and perception of Treasury securities have become a focal point of concern. The discourse emphasizes the so-called toxic nature of Treasury debt instruments: a concern grounded in a rising-rate environment that erodes the value of existing bonds as new issues offer higher yields. The comparison between fixed-income securities and alternative stores of value has taken on renewed urgency. The 10-year Treasury yield, hovering around 4.6 percent, is evaluated against expectations for inflation and the degree to which inflation trends will persist. The official Consumer Price Index (CPI) has shown a 3.7 percent reading in recent updates, but observers question the accuracy of such measurements and point to the lived reality of higher cost-of-living pressures. Personal experience, such as everyday shopping, is cited by many as evidence that actual inflation runs hotter than government statistics suggest. This divergence fuels ongoing debate about whether Treasuries can remain a safe haven in a climate of rising rates, rising deficits, and a fragile liquidity backdrop.

The risks associated with Yield Curve Control are not purely theoretical. The central banks’ efforts to manage interest rates are seen by many observers as enabling a broader monetary experimentation that could have sweeping consequences for the entire financial system. The argument is that YCC is a step toward an undisclosed and potentially large-scale reallocation of risk and value across asset classes, including equities, real estate, and bonds. The concern is that once government policy begins to shape the cost of money with the aim of stabilizing debt service costs, it becomes increasingly difficult to return to a truly free-market regime. In such a scenario, asset prices may become decoupled from underlying economic fundamentals, creating bubbles or inflating riskier surges that could unwind abruptly.

A critical element of this narrative is the performance of Treasury bonds during a period of rising interest rates. The market has witnessed a dramatic decline in the value of Treasuries, with some instruments experiencing significant drawdowns. Estimates suggest that Treasury bonds have declined in value by roughly 40–50 percent over a multi-year horizon, while the long-duration securities have suffered even larger losses. This drop in value has real consequences for investors who rely on Treasuries for income and principal preservation, including widows, orphans, and retirees who prefer stable, reliable returns. The consequence is a renewed search for safe havens and diversified income strategies in an environment where conventional gold standard bonds no longer provide the same degree of security they once did. The performance gap between Treasuries and riskier assets such as cryptocurrencies or high-growth equities has led to renewed discussions about portfolio diversification and the role of alternative assets in a balanced financial plan.

From a market perspective, the magnitude of the Treasury market adds to the complexity. The U.S. Treasury market is widely recognized for its size, with estimates placing the overall market cap around $24 trillion. Against that backdrop, investors hold substantial unrealized losses over a multi-year stretch, in the neighborhood of more than $16 trillion in open losses over roughly three and a half years. The scale of these losses is not merely a numerical curiosity; it has meaningful implications for the cost of capital, the willingness of investors to participate, and the broader confidence in sovereign debt as a foundation of the financial system. The combination of heavy deficits, rising rates, and the prospect of yield-curve management means the bond market sits at a crossroads, with potential consequences rippling through housing, corporate finance, and consumer credit.

The discussion around yield curve control also raises questions about the path forward for inflation, asset prices, and fiscal credibility. Proponents of aggressive policy action argue that central banks must do whatever it takes to stabilize growth and prevent a deeper downturn, particularly in the face of two ongoing conflicts and a global financing backdrop shaped by de-dollarization pressures. Critics respond by warning that such interventions risk greater monetary debasement, which can undermine confidence in the currency and spur a further retreat from traditional savings instruments. In this sense, YCC is not just a technical policy tool; it is a signal about the broader trajectory of the global monetary system and the degree to which policymakers are prepared to sacrifice the autonomy of free markets to preserve financial stability.

Against this backdrop, the WeWork bankruptcy stands as a vivid and concrete case study of the real-world consequences of a global macro environment under strain. WeWork, a giant in the co-working and commercial real estate sector, recently filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in New Jersey. The company operates an expansive footprint—more than 44 million square feet of office space across roughly 779 locations worldwide—and once boasted a market capitalization near $47 billion at its peak. The bankruptcy filing reflects a dramatic reconsideration of value in the commercial real estate space and signals broader stress within the labor market and the economic system as a whole. WeWork’s restructuring plan involves negotiating with secured creditors and trimming underperforming leases, representing a strategic shift that reverberates across the U.S. and Canadian segments of its operations.

Preliminary disclosures show a stark mismatch between liabilities and assets: about $18.65 billion in liabilities compared with roughly $15.06 billion in assets. The resulting valuation meltdown—nearly a $50 billion erosion in perceived enterprise value—reads as a pointed illustration of the fragility that can accompany lofty valuations in a high-debt, high-rate environment. This development is more than a corporate insolvency narrative; it is a lens into the resilience of commercial real estate and the practical consequences of shifting demand and rising financing costs in a post-pandemic economy. The WeWork case thus becomes a cautionary tale about leverage, cash flows, and the vulnerability of real-estate-heavy business models to macroeconomic strains and shifting work paradigms.

Taken together, the unfolding stories of widening deficits, elevated debt, and a volatile bond market illuminate a central tension in today’s economy: the need to reconcile fiscal and monetary policies with the realities of a world characterized by higher rates, slower growth in certain sectors, and a labor market that remains uneven. The accumulation of debt, the management of the yield curve, and the health of the commercial real estate sector are not isolated threads; they form an interconnected web that influences everything from personal savings decisions to corporate investment plans and long-run macroeconomic stability. As policymakers continue to navigate these challenges, investors and households alike must weigh the competing claims of fiscal generosity, monetary restraint, and market discipline, recognizing that the choices made in the near term will reverberate through the economy for years to come.

Below the surface, one clear takeaway stands out: when deficits rise and debt burdens grow, the pressure mounts on the tools that keep credit flowing and growth supported. The current environment makes clear that the traditional playbook—relying on steady growth and stable inflation—faces a more complicated set of headwinds than in the recent past. The stakes are high, and the decisions taken by policymakers, financiers, and business leaders will shape the trajectory of the economy, the health of the financial markets, and the everyday financial security of individuals across the country. In this complicated landscape, questions about the sustainability of debt, the credibility of tax receipts, and the future of market-based price discovery remain central to any serious discussion about the road ahead.

In the face of these evolving dynamics, a growing emphasis on data-driven analysis and risk-aware decision-making has sharpened the focus on how investors and institutions interpret signals from debt markets, inflation metrics, and policy intentions. The narrative presented here underscores not only the scale of the challenges but also the interconnectedness of fiscal policy, monetary policy, and real-economy outcomes. As observers search for clarity, one message remains consistent: the path forward requires careful calibration of policy choices, prudent risk management, and a vigilant assessment of how changes in debt, deficits, and yields translate into tangible implications for growth, employment, and household financial security.

Conclusion: The debt trajectory, policy maneuvers, and corporate stress all signal that we are in a period of heightened sensitivity to how fiscal and monetary decisions interact with the real economy. As deficits rise and the debt load expands, the pressure on tax revenue, interest costs, and market confidence intensifies. The WeWork episode shows how quickly financial conditions can tighten when financing conditions become constrained and demand shifts in the real estate sector. In this environment, the emphasis on trend-based analysis, risk management, and disciplined trading approaches—augmented by artificial intelligence tools—becomes increasingly essential for navigating volatility, protecting capital, and identifying opportunities amid ongoing market disruption. The economic landscape is shifting, and those who understand the evolving dynamics—debt, deficits, yields, and policy tools—will be better positioned to respond to the changes as they unfold. The road ahead remains uncertain, but the logic of caution, strategic planning, and disciplined execution in the face of a complex macro backdrop stands out as a core principle for investors, policymakers, and households alike.